Escaping the Content Trap*

My name is Lars K Jensen, and I work with journalism and editorial insights as the Audience Development Lead at Berlingske Media in Denmark.

Feel free to connect on LinkedIn and say hi.

Executive summary

(Written by ChatGPT and approved by the author.)

The belief that audiences pay for content is misleading. Journalism’s real value lies in the outcomes and connections it creates. People don’t seek stories for their own sake — they want solutions, understanding, and community. Content is only the vehicle for that value. When publishing moved online, many mistook articles for the product itself, overlooking the deeper role journalism plays in connecting people and helping them navigate their world.

Seeing journalism through the lens of connections opens new strategic ground. VG’s “Hitchhiker’s Central” during the 2010 ash cloud crisis showed what happens when publishers act as enablers, not just storytellers. Readers didn’t need more coverage — they needed help getting home. That kind of utility and community-building points to what truly drives engagement and loyalty: creating spaces where people can participate and feel part of something larger.

Frameworks like Jobs To Be Done and User Needs make this shift practical. They focus on what audiences are trying to achieve and how journalism can serve those needs. Adopting them means redefining the “core” of journalism — from producing stories to building meaningful human connections. Escaping the content trap isn’t about abandoning storytelling; it’s about remembering what stories are for.

🎧 Looking for the audio version?

I've been experimenting with adding audio versions (by using ElevenLabs' AI voices) to some of the recent articles in this newsletter.

This time the test is... to not have an audio version. Would you like one? Let me know at lars@larskjensen.dk.

I've been wanting to write this post for some time. Both because it's about an important topic for our industry – but also because it sums up how my thinking and approach to the development of journalism has evolved over the years.

The itch to do this write-up intensified when I read Patrick Boehler's absolutely amazing "Stop pretending journalism matters on its own".

He writes about how we as publishers are not trading journalism or stories. Instead it's about the value, our journalism and stories provide to our audiences, communities and customers.

Patrick writes:

"The strongest media organizations I've encountered understand that people don't seek out journalism for journalism's sake - they want solutions to problems, ways to improve their lives, recognition, community."

This is what it's really about. Understanding our value proposition to the people paying us (with their money, attention and time). Content is a vehicle for that. A means, not the actual value.

And that way of looking at it is actually perfectly in line with what journalism is, as Patrick notes:

"This isn't about abandoning the craft of Journalism - the skills of critically and empathically seeing, observing, understanding, and conveying remain vital. But these skills must serve genuine human needs, not institutional self-preservation."

The focus on content and articles partly has its roots in a limiting view of what journalism and publishers have to offer – and a large part of it stems from when newspapers moved online.

We thought that what people paid for was the content and the articles we put into those papers – so we made those into our core product and offering; thus starting the "institutional self-preservation", Patrick writes about.

As I mentioned in a LinkedIn post, Patrick's thoughts reminded me of an awesome book I read a little less than a decade ago. It's called The Content Trap and is written by Harvard professor Bharat Anand.

The premise is simple: If you think that content is what people are paying you for and how you should position yourself, you are caught in the content trap.

Instead, Anand argues, we should focus on the connections we are establishing.

He talks about three kind of connections:

- User connections

- Product Connections

- Functional connections

Here, I will focus on the first type (user connections) because I think that's the most important one – yet also the one that is the easiest to miss.

(If you are curious about the two other types of connections, Mitch Rencher has a write-up on the book as a whole.)

Leading us astray

I first came across Bharat Anand and his book in a 2016 episode of Harvard Business Review's IdeaCast podcast titled "How Focusing on Content Leads the Media Astray".

What really caught my attention was when he talked about what happened when newspapers went online – and how the classified ads played a big role in what then happened (it's a long quote, but it's worth it):

"It turns out, if you take a step back and you ask the question what was the impact of the internet on newspapers? The story we often instinctively might come up with is online news is faster, it’s cheaper, it has more variety, it has a rich media, it’s personalized. So online news actually really destroyed print news.

It turns out, that story is more or less wrong. By now, what we know is the main reason newspapers were destroyed had much less to do with the content they were offering, and much more to do with another revenue stream for newspapers, which was classified advertising, which accounts for about 40% of the revenue of a typical newspaper, more than half of the profits. So classifieds fundamentally, is a connected product. The more buyers you have, the more sellers who list. The more sellers, the more buyers. So they have these feedback loops.

And one of the implications is that for connected products or network products– as we might call them– when you win, you win big. You win the entire market. When you lose on the other hand– like most newspapers did in classifieds– you lose the entire revenue stream. So that philosophy in some sense, was something that they recognized pretty early on. It then infiltrated into the newsroom.

And as you said, we sort of see this philosophy almost as a countervailing force, or an approach to the traditional organization in media, which is really focused around producing the best content. And that’s trap number one, which I describe in the book, that this idea of producing the best content in a digital world might actually be the wrong strategy.

[...] so I think for news organizations, the natural instinct is if there’s something wrong with our bottom line, it must be something to do with news. After all, we called it a newspaper, right? We didn’t call it a classified ad paper. The folks who sit at the center of these organizations are the editors and the journalists in the newsroom. So that’s the instinct.

I think what’s particularly interesting is news was probably always a social good. It’s just that we never observed the social nature, right? We used to produce content, and then the conversations would happen. Now, it turns out we can actually trigger, curate, see those conversations happening online. So it’s just come to the fore.

In his book, Anand dives deeper into the role of classifieds and delivers his point in plain English:

"The Internet didn’t kill news; it destroyed the classifieds subsidy. Where news organizations went wrong was not in failing to deliver faster, cheaper, better news online—to believe that is to fall into the Content Trap—but in failing to protect the classifieds subsidy or to profitably manage its migration online.

Papers were beaten to the punch in capturing user connections in the digital arena.

Miss that connection, as most newspapers did, and no matter how robust or creative your online news strategy, you would be trying to solve the wrong problem."

Okay, enough talk about the classifieds and ad markets – but it's clear that a large part of what made newspaper businesses work where the connections they fostered.

And that should influence how you strategize and plan for the future as a publisher. Anand writes:

"Business strategy is about two questions: where should you play, and how will you win. Finding the right answers requires making your product right, knowing your consumers, and understanding how these are changing in your market.

But, increasingly, I will argue, that’s not enough. Understanding your landscape requires thinking not just about products and consumers—as is the trend—but also about the connections among them. Understanding how to win requires looking not to other organizations for answers—another trend—but to the connections among all the activities inside your own."

The good news for newspapers and publishers is that they are inherently about connections; and connections between users. Let's try to look at journalism through a prism of connections.

Conversations

Quoting The Cluetrain Manifesto, I believe that "markets are conversations" - and the markets we operate in as publishers are no different. This is why conversations are so integral to both us and our audiences.

When I'm giving talks about this, I usually reference a quote from a talk by Tav Klitgaard, the CEO of Danish media startup Zetland, a few years ago:

"Being a Zetland member is about helping you join interesting conversations that are already happening – or to start interesting conversations with others."

It's really that simple – and it's a clear and easy-to-understand raison d'être to live by.

Obviously you can't substitute an entire strategy, vision, value proposition and positioning statement with that single sentence. But it gets your audience and their content (and their connections!) baked into your organisation and your journalism in a pretty neat way.

And let's talk about "most read" lists for a moment. A lot of us don't like them, but they work – and they work for a reason.

People don't click to read the most read stories to just to read what gets the most clicks and has the sauciest headline.

People click to read the most-read stories because they want to know what others like them are reading and interested in. They basically want to know what others know, and one of the reasons for that is to participate in conversations, as Tav Klitgaard and Bharat Anand mentions.

So a list of your most read articles isn't just a list of clickbaits articles. It's your audience's attempt at trying to stay on top of what others are looking at so as to avoid being left out of a conversation.

Nobody wants to be the one that goes "what happened?" when the rest of the office is discussing an important event or news story.

It's more about connections and conversations – and less about the content.

Communities making a comeback

This is also one of the reasons why publishers are looking into communities and becoming platforms for conversations once again.

Okay, it's also because the large platforms and tech companies aren't the traffic guarantees they once where, so publishers have to think about how they can get stronger, more direct relations with their users and audiences.

And it's a trend you shouldn't ignore – it's real, and it's happening now.

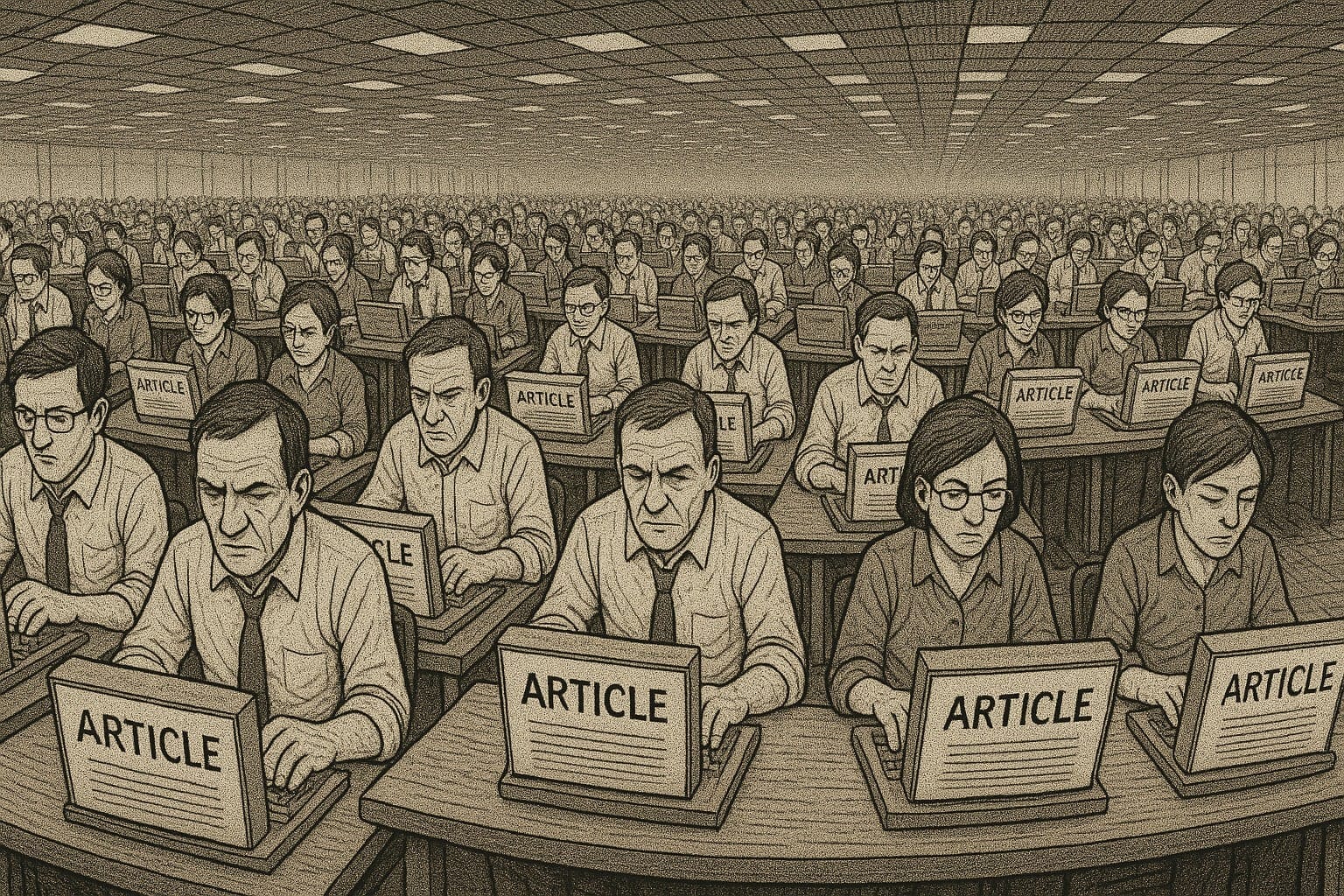

In July, WAN-IFRA published the latest edition of their World News Media Congress Playbook, titled "7 priorities where publishers must excel" – and the 5th is "Next-level engagement: Shifting focus from audience to community":

Looking at the list of the 2025 Nieman Lab predictions, the words "communities" and "community" appear 15 times combined (although, both in terms of "digital communities" and local communities in the real world – and the industry is constantly talking about engagement, conversations, comments; all things that you'd expect from a community.

It's also worth noting that publishers are increasingly looking to events as a part of what they are offering their audiences. Both to reward current subscribers (retention) – and to draw new subscribers, as Digital Content Next has written about.

So we are slowly realizing that there might be more to news publishing in 2025 than the stories we publish.

Still, some community conversations seem to linger around content, with reader comments probably being the best example – even though some publishers will have some mixed experiences – and some, like Germany's Der Spiegel, making user comments more manageable and meaningful.

But how can it look when publishers branch out and make something that is not content?

Avoiding the ash cloud

One of the examples from Arand's book is "Hitchhiker's Central" by Norway's VG.

In April 2010 the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajökull went into eruption, sending an ash cloud up in the air which grounded flights in most of the European airspace for several days.

Instead of just writing about the ash clouds (as a lot of publishers and newspapers did), VG set out to something about it.

Nieman Reports has an excerpt from The Content Trap, where Espen Egil Hansen (then editor at VG and now Vice President of the board at Denmark's JFM media group) says:

"It wasn’t news. It was a tool. It was like a marketplace. 'I have a car, I am going to Trondheim, if you want a ride, let me know and we can share the petrol.' Or, 'I am stuck here, need to get there.' We would hide their phone number but still make the connection between readers. That’s all we were doing, connecting people.

It took off. We were connecting people by the thousands, not only in Norway but in the whole of Europe and beyond. There were bus trips organized through this from all the capitals in Europe—Spain, Bulgaria, France, everywhere. We were sending people to weddings, to funerals. We were getting children home. We sent a cat to a cat exhibition in Finland. It was just amazing. And then people started sending pictures to the newsroom to say thank you. 'We are on our way to Bulgaria, thank you, VG.'

So two things happened. We got pictures for an ongoing news story that involved basically everyone. And because people sent the pictures with their phones, we had their numbers and could interview them. It strengthened our reputation.

The sentence "it wasn't news" is really at the core of what this is about. People didn't need more articles about the ash cloud; they needed help in how they could still travel and navigate in their lives despite something happening outside of everyone's control.

VG saw that – and they delivered it.

Obviously, most publishers can't build tools like "Hitchhiker's Central" on a daily, weekly or perhaps even monthly basis (some definitely could, I would argue).

Content and stories still are huge parts of the game and regular offering – and we have (finally!) begun to talk about what stories are doing for our audience and less about what the stories are in themselves.

Jobs To Be Done

If you work with Product Management, you probably already know about the Jobs To Be Done approach.

In short, it's about:

- Identifying the jobs that your users have and are trying to get done.

- Find out what they are using (or "hiring") to do that.

- Identify problems and roadblocks which you can solve.

- Build your value proposition around what you have learned and what you can do.

- Launch it, market it and make money 🤪

I personally like this approach because it makes the whole thing a lot more actionable than just working with target audiences.

As Clayton Christensen and others wrote in a MIT Sloan Management Review article on Jobs To Be Done back in 2007 (with my emphasis):

"Product and customer characteristics are poor indicators of customer behavior, because from the customer’s perspective that is not how markets are structured. Customers’ purchase decisions don’t necessarily conform to those of the 'average' customer in their demographic; nor do they confine the search for solutions within a product category.

Rather, customers just find themselves needing to get things done. When customers find that they need to get a job done, they 'hire' products or services to do the job. This means that marketers need to understand the jobs that arise in customers’ lives for which their products might be hired."

This is probably my favourite quote as it adresses something important about target groups and demographics – and how product categories become more fluid.

If you, for instance, need to find out who won an election, football match or something else, news publishers are just one of the sources you can go to.

And the playing field is changing rapidly, with Artificial Intelligence both in the form of bots and Google's summaries leaving the user with less and less need to navigate to an actual article or even publisher websites.

So the product categories become much harder to separate.

Jobs To Be Done is about focusing on the user's context and then expanding from there. As Steve Jobs once said (even though he wasn't talking specifically about Jobs To Be Done):

"You’ve got to start with the customer experience and work backwards to the technology. You can’t start with the technology and try to figure out where you’re going to try and sell it."

If you are a publisher try to look at some of your best performing and most impactful stories through the Jobs To Be Done lens:

- What kind of "jobs" do you think your reporting (however you did and presented it) helped your audience "get done"?

- Do you think they maybe have some other jobs which you aren't addressing – or probably could become even better at?

- How can you improve – by making it easier and better for the user?

That's the kind of thinking that can limit the gaps between you and your audience.

There are a lot of great writings on Jobs To Be Done out there (I've previously read this book which I enjoyed) so if you are interested there's plenty of content (😉) to dive into.

Nikita Roy from Newsroom Robots also mentioned Jobs To Be Done during her talk (in fact "call to action from the industry" would probably be a better description 😊) at the Nordia AI in Media Summit 2024 in Copenhagen which I reflected on then.

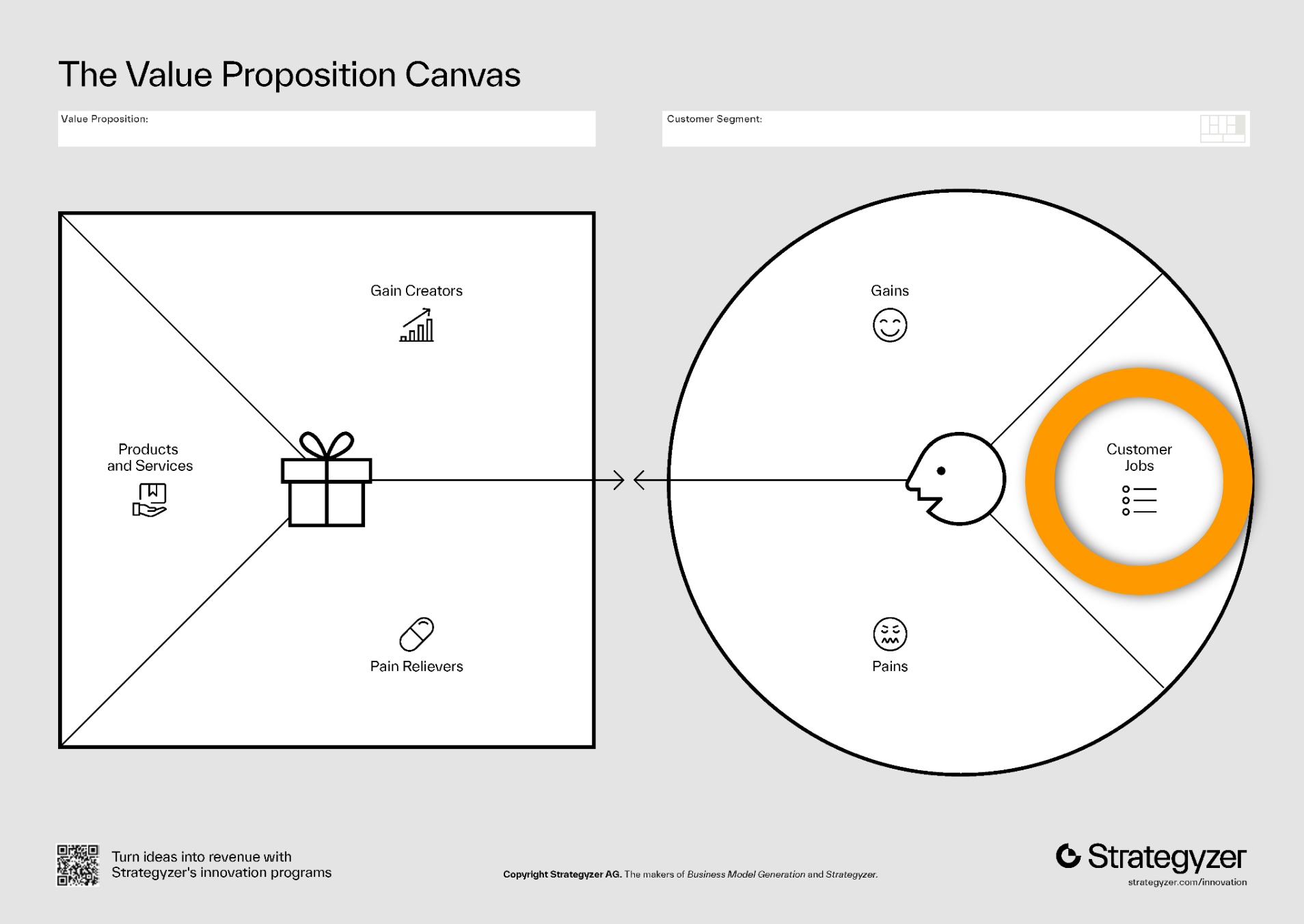

Personally, I prefer to use Jobs To Be Done in combination with the Value Proposition Canvas (which I like to call a baby brother or sister to the Business Model Canvas) – as Jobs To Be Done on its own can become huge:

But, sadly, it's really hard to adopt and scale Value Proposition Canvas and Jobs To Be Done into a newsroom which need to publish something every day (maybe even every hour).

Believe me, I've tried.

So you need something than can fit into and rhyme with how journalism is being produced and distributed.

User needs

The core approach in Jobs To Be Done (that people are trying to accomplish something) is also where the increasingly popular user needs approach comes from.

First developed in 2018 by Dmitry Shishkin (then digital development editor at BBC World Service, now strategic editorial adviser at Ringier) and later refined by Shishkin and Smartocto into a 2.0 model, the user needs method is about establishing a set of needs which you then use as a prism to analyze, develop and present your journalism.

So basically, it's Jobs To Be Done coded into a newsroom-friendly structure – which tells you a lot about why user needs are so important and talked-about in our industry.

I've written a series of articles on user needs in this newsletter – and as with Jobs To Be Done there are loads of brilliant things waiting for you on the web.

When working with user needs you focus less on the content and more on what it actually does for the user – and helps your audience accomplish. (Thus helping you avoid some of the worse pitfalls of the content trap.)

I have tried getting Value Proposition Canvas, Jobs To Be Done and user needs adopted and implemented in newsrooms – and I can tell you that the user needs approach is a much better fit and scale a lot better into newsrooms than any of the other methods.

Think of it as either building a value proposition based on your audience's Jobs To Be Done or escaping the content trap at scale (and speed, hopefully). The end goal is the same, but the means are very different.

The user needs 2.0 model consists of the following needs:

- Update me

- Keep me Engaged

- Educate me

- Give me perspective

- Divert me

- Inspire me

- Connect me

- Help me

...but some publishers are instead using their own models based (I hope) on their own analyses and research into both their journalism and audiences.

The Atlantic's executive director of audience research has wrote about their work on developing their own model back in 2018 and maybe you've read my article on our implementation of the Wall Street Journal model (based on the first BBC model).

Both models have been incorporated into the 2.0 model by Shishkin and Smartocto – but try to find the approach that suits you best. I would argue that everyone publishing or doing any form of communication can benefit immensely from working with user needs.

When done right, you start with your audience and their "needs" and then you can develop stories (or different ways of reaching and engaging your audience!) based on that knowledge and your own analyses.

And thinking in user needs should influence more than just the content being produced. As publishers start thinking in communities, we should probably start thinking about user needs in communities as well.

And how may user needs help publishers when doing events? How can events help the people attending with the needs and Jobs To Be Done they have?

Using user needs to analyze and develop content and stories is really just the first wave of how this approach to journalism and audience can transform our industry.

Adopting user needs may sound pretty simple and easy to get started on – and in many ways it is.

When I introduce user needs to newsroom the reaction is usually "is that it?" – and yeah, that is it. It's not rocket science; it's journalism.

Which also means that the hard part isn't talking about it. It's doing something about it that causes headaches around the industry.

Why is it so hard?

I've spent almost two decades in this industry – and all of them in digital journalism, where I like to think that I have almost tried every kind of launch, redesign, workshop, sprint and audience initaitive.

And even though I have worked with some of the best and most curious people who want to know how their journalism is consumed and can be as valuable as possible – we still end up talking about content and stories.

And I'm guilty of that as well 🙋🏼♂️

I think it comes from our view of our past, as publishers of news and not as facilitators and makers of connections. We looked at what we served to our audiences in the print world and then doubled down on the part of it we make ourselves – and the part of it we understand the best.

Content and stories.

As with so many other things it's a mindset thing. A culture ting.

It takes a certain newsroom culture and approach to ideas and journalism in general (and collaboration!) to come up with something like "Hitchhiker's Central" as VG did.

It requires that you take a step back from producing yet more content – and think about how and where you can make the biggest difference to your audiences.

Some may see this as being in conflict with the focus on the core approach a lot of publishers are following (for very good reasons, I might add). But what is our core?

Back in 2016, Anand said the following on the HBR podcast:

"[...] for a long time, the major prescription that we used to offer companies was focus on what you do best. Narrow your product focus. Think about your core competence. In a sense, that’s true, particularly in mature businesses. You want to really think about what you do well. On the other hand, when growth slows down, or in digital worlds where value can often be redistributed pretty seamlessly across parts of the ecosystem, you want to think more expansively."

A 2016 Harvard Business Review article titled "How to Pull Your Company Out of a Tailspin" tells us (in a very HBR kind of way) to focus on "the core of the core".

Yes, that sounds like bullshit corporate newspeak (pardon my French), but if we actually dive a bit into it, what would it mean for us as publishers and newspapers?

If the core of what we do is journalism – what then is the core of journalism?

Content?

Information?

Knowledge?

Impact?

Conversations?

Connections?

My name is Lars K Jensen, and I work with journalism and editorial insights as the Audience Development Lead at Berlingske Media in Denmark.

Feel free to connect on LinkedIn and say hi.

💌 You've made it this far. If you find it interesting, please consider following the newsletter.

*For those of you that don't know it, the title is a reference to Melissa Perri's 2018 book "Escaping the Build Trap" on product management.